I’ve just finished reading Sebastian Seung’s book “Connectome: How the Brain’s Wiring Makes Us Who We Are,” which introduced me to the concept of neuronal connectomics.

We all agree that the brain is a network with many nodes connected by numerous connections. Olaf Sporns proposed the term “Connectome” to describe this brain network. We naturally think of neurons as the nodes and synapses as the edges. Seung refers to this as the “Neuronal Connectome.” However, this network contains too many nodes and edges to analyze easily. To address this complexity, Sporns simplifies it. Many complex networks have clusters of nodes. If we zoom out a bit, these clusters can be treated as larger nodes, simplifying the network. Seung refers to this as the “Regional Connectome.” A further simplification groups nodes by neuron types, which Seung calls the “Neuron Type Connectome.” He argues that although simplified versions are useful, studying the original, the Neuronal Connectome, is essential for understanding autobiographical memory and other unique aspects of our personal identities.

Personally, I would like to study the simplified version–the Regional Connectome–first. According to Jeff Hawkins’s “A Thousand Brains,” which I read earlier, there is a natural cluster in our brains called the cortical column. A region, as divided by Brodmann, usually contains several similar cortical columns. The pyramidal neuron in a cortical column extends its axons into the white matter, connecting to another cortical column in a different region. These axons often bundle together to form fiber tracts, also known as white-matter pathways. Understanding these could reveal much about personality, mathematical ability, autism, and other general features. However, for deeper insights, neuronal connectomics would provide the details within a cortical column and offer more fundamental explanations about the brain. This is the inevitable future of the field.

Seung measures the Neuronal Connectome using Serial Electron Microscopy (SEM). This involves hardening the tissue with epoxy resin (plastination), slicing it into very thin pieces, and then photographing these slices with an electron microscope. A computer then reconstructs the three-dimensional structures from these images.

Seung’s approach diverges from traditional hypothesis-driven scientific methods. He describes his approach as data-driven, hypothesis-free, inductive research: (1) collect a vast amount of data, (2) analyze it to detect patterns, and (3) formulate hypotheses based on these patterns. I believe this method is as valid as hypothesis-driven research because it can generate hypotheses that guide future inquiry.

In 1986, the connectome of the hermaphroditic C. elegans was mapped, featuring exactly 302 neurons and approximately 7,000 chemical synapses, along with some gap junctions and neuromuscular junctions. This work on C. elegans serves as a stepping stone toward understanding the human connectome, which is orders of magnitude more complex, with an estimated 100 billion neurons and synapses numbering in the order of 100 trillion to 1,000 trillion.

The challenges in capturing the human connectome are monumental. Yet, I wish Seung the best of luck–not only in obtaining this complex data but also in analyzing it. Advances in large language models (LLMs) offer promising methods for automatically analyzing one-dimensional data like text, genes, and protein sequences. However, new breakthroughs in fields dealing with graph data are needed to analyze complex networks like the human connectome effectively. At present, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are not powerful enough for this task.

Although we are far from having a complete human connectome, Seung’s book has nonetheless introduced many intriguing concepts to me. One of my favorites is Seung’s metaphor comparing the brain’s structure (the synapses connecting neurons) to a riverbed and the brain’s activity (consciousness) to the water flowing through it. The structure dictates the flow of activity, and the activity reshapes the structure. This led me to appreciate the dual nature of brain study: one can examine living brains to understand moment-to-moment dynamics using techniques like fMRI, or focus on the more stable structural aspects found in deceased brains.

Understanding both the dynamic activity and the stable structure allows for a more comprehensive explanation of phenomena like short-term and long-term memory. For example, when an assembly of neurons spikes, this activity can represent transient short-term memory. The repetition of these spikes can lead to changes in the synapses, perhaps through Hebbian mechanisms (“fire together, wire together”), and these stable changes can be considered long-term memory.

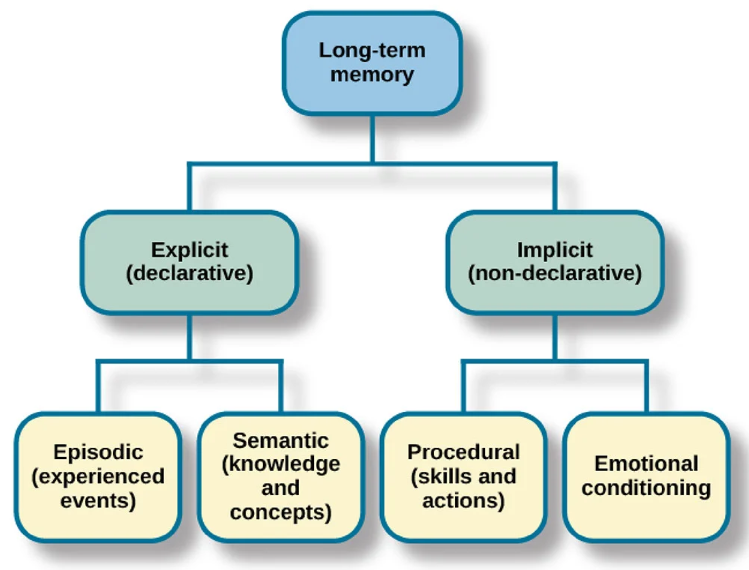

Different types of structures could exist: neuron assemblies and synaptic chains. A neuron assembly could correspond to a concept, a fact, a feeling, or a specific reaction–forming our semantic or emotional memory. A chain of these assemblies could create a synaptic chain, corresponding to a sequence of concepts or actions, which would be our episodic or procedural memory. Both are forms of long-term memory, as shown in the following diagram.

Source: https://www.simplypsychology.org/long-term-memory.html

Understanding this also helps us see why richer information is easier to remember. For instance, when memorizing a list of random items, envisioning walking through a series of rooms with these items placed in different locations increases the redundancy of each item’s representation, corresponding to larger assemblies, thus the connections between those larger assemblies are easier to find and strengthen, making it easier to remember.

Another fascinating concept is Neural Darwinism, which posits that synapses are formed randomly and continuously. These synapses then either strengthen through use or weaken and eventually disappear through disuse, a mechanism that could be regulated by Hebbian rules. Understanding this process has significant implications, as it could lead to molecular interventions that promote learning–or even forgetting.

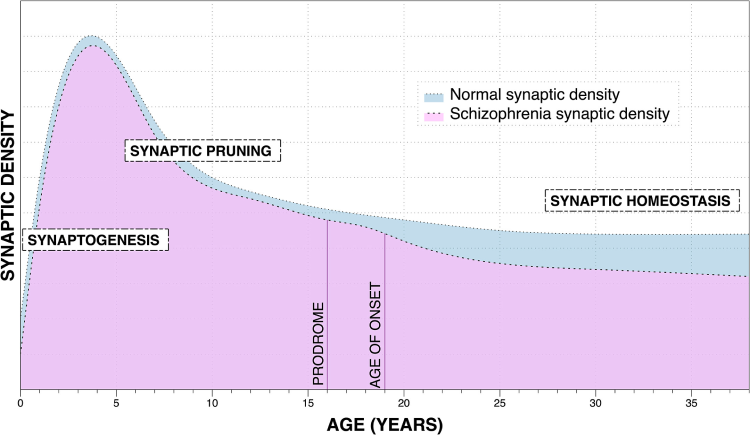

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S000632232201366X

This figure is from a study of schizophrenia, but let’s focus on the blue area indicating ‘Normal Synaptic Density.’ As we can see, the phase of synaptogenesis leaves a baby with a high level of synaptic density, which later undergoes significant reduction during synaptic pruning. According to Neural Darwinism, this process allows a baby’s brain to maximize its learning potential at a young age while also shedding the unused synapses.

In conclusion, this book has expanded my understanding of the concept of connectome, the structure of our brains, and it has also introduced me to a variety of intriguing concepts. I look forward to exploring them in greater depth in the future.

Any feedback? We can discuss it under this Tweet.